Circadian-Informed Lighting

"Circadian Lighting" may sound like an over-used buzzword these days - but peel back the polish and you'll uncover something real: A new dimension in lighting design, grounded not in fleeting trends, but physiology.

Let's take a quick look at the following:

1. What is circadian lighting, really?

Circadian lighting uses electric light to support the body’s internal clock, especially your sleep/wake cycle, hormonal rhythms and other biological processes. It mimics the natural patterns of daylight to help keep these systems in sync.

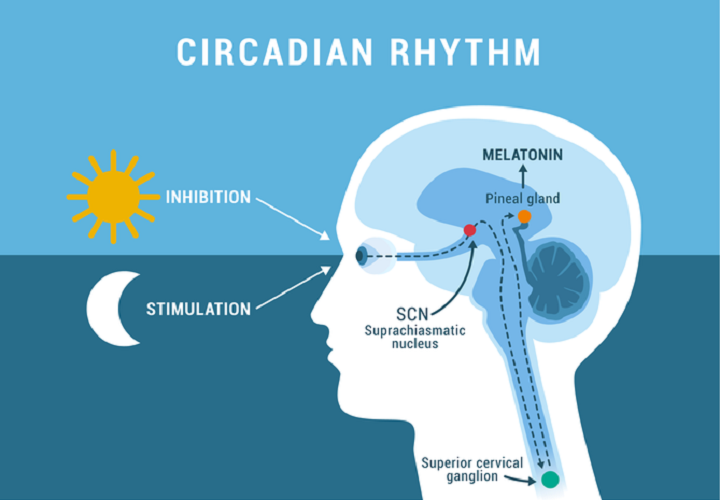

Light has an inhibitory effect on melatonin production, meaning it suppresses production of this sleep-promoting hormone. In contrast, darkness allows melatonin levels to rise by removing that inhibition. This daily rhythm in melatonin is one of the key signals that regulates sleep, mood, and alertness. These effects are largely driven by a special type of light-sensitive cells in the retina called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, or ipRGCs for short. These cells contain a photopigment called melanopsin, which is especially sensitive to blue light.

In addition to regulating our internal clock, ipRGCs also help maintain pupil constriction in bright light. Rods and cones trigger the initial response, but ipRGCs sustain it during prolonged exposure, helping protect the retina and reduce glare sensitivity in bright environments. |

|

|  |

| Unlike rods and cones, which enable us to see, ipRGCs don’t directly(*) contribute to vision. Instead, they measure ambient light levels and send timing signals to brain regions that regulate sleep, mood, alertness, and hormone release. The most important of these regions is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), often called the body’s master clock. Signals from the SCN travel through a complex pathway that involves SCG (the superior cervical ganglion) and eventually reach pineal gland, which adjusts melatonin production accordingly. |  |

This is why it’s important to distinguish between what we see and what our body senses: A room may look dim to your eyes but may still expose you to enough short-wavelength light to delay melatonin production and shift your internal clock. Circadian lighting design aims to respect this distinction and create healthier, more biologically supportive environments.

This is also why CIE now recommends the use of the term "Integrative Lighting" for lighting that considers both visual and non-visual pathways.

(*) While ipRGCs don’t form images in the traditional sense, they do contribute to how we perceive brightness. They interact with rods and cones via complex retinal circuits, so no photoreceptor works in isolation. ipRGCs receive input from rods and cones - and send signals back, blurring the line between visual and non-visual effects. They’re also not a single cell type, but a family of subtypes, each specialized for different tasks. Understanding their exact role is still an active area of research.

2. Think of it like a dose

Circadian lighting isn’t about simply increasing the amount of light - it’s about delivering the right kind of light at the right time. A helpful way to think about it is like medication: it's not about taking more, but about taking the correct dose.

Here’s how the analogy works:

-

Illuminance × Duration → How many tablets you take per day

-

Spectral Content → How many milligrams of the active ingredient are in each tablet

-

Timing → Whether you take the tablet in the morning or at night

If you take the wrong dose or take it at the wrong time, you may get the opposite effect of what you intended.

3. Is circadian lighting relevant in Australia and New Zealand?

When people hear about circadian lighting, they often assume it’s mainly useful in places like northern Europe, where long, dark winters disrupt natural light cycles. It’s an understandable assumption. After all, if you live somewhere sunny, how much difference can lighting really make?

Quite a lot, it turns out.

Circadian-informed lighting isn’t just for far-northern climates or scientific journals. It’s highly relevant to how we live and function indoors—where we now spend the overwhelming majority of our time.

|  |

Like most developed nations, Australians and New Zealanders spend 80–100% of their time indoors, often in spaces where artificial light dominates (Source: Victorian Department of Health). And that light often fails to support our biological rhythms.

Over the past few decades, neuroscience has shown just how profoundly light influences our sleep, mood, alertness, and well-being. Yet this understanding is still rarely reflected in mainstream lighting design.

The result? Many of our homes, offices, schools, and hospitals are still lit in ways that work against how our brains and bodies are wired to respond to light.

4. Why simply meeting the standards isn’t enough

Walk into almost any office, home, hospital or aged-care facility that meets current lighting standards—like AS/NZS 1680—and you might assume the lighting is doing its job. On paper, it is. But in reality, it’s falling short—especially when it comes to supporting our health.

Modern neuroscience has shown us that light influences far more than just vision. It also affects our internal biological clock—our circadian system—through non-visual pathways that respond to specific qualities of light, particularly blue-enriched wavelengths measured as Melanopic Equivalent Daylight Illuminance (Melanopic EDI).

Most regularly occupied spaces today provide lighting levels far below what’s needed to support healthy circadian rhythms. Offices typically deliver horizontal illuminance between 200 and 500 lux. In homes, it’s often closer to 100 lux. In aged-care facilities—where circadian health is especially critical—light levels are usually even lower, more inconsistent, and less supportive of residents' biological needs.

In short, compliance with the standard doesn’t mean the lighting is optimal for human health. To design truly human-centric spaces, we need to go beyond the minimum and start aligning lighting with how people actually function—visually, biologically, and behaviourally.

5. What we’re doing at Eagle Lighting

At Eagle Lighting, we believe light should do more than meet technical benchmarks - it should contribute to human wellbeing. That’s why circadian lighting isn’t just a catchphrase to us; it’s a guiding design principle backed by science.

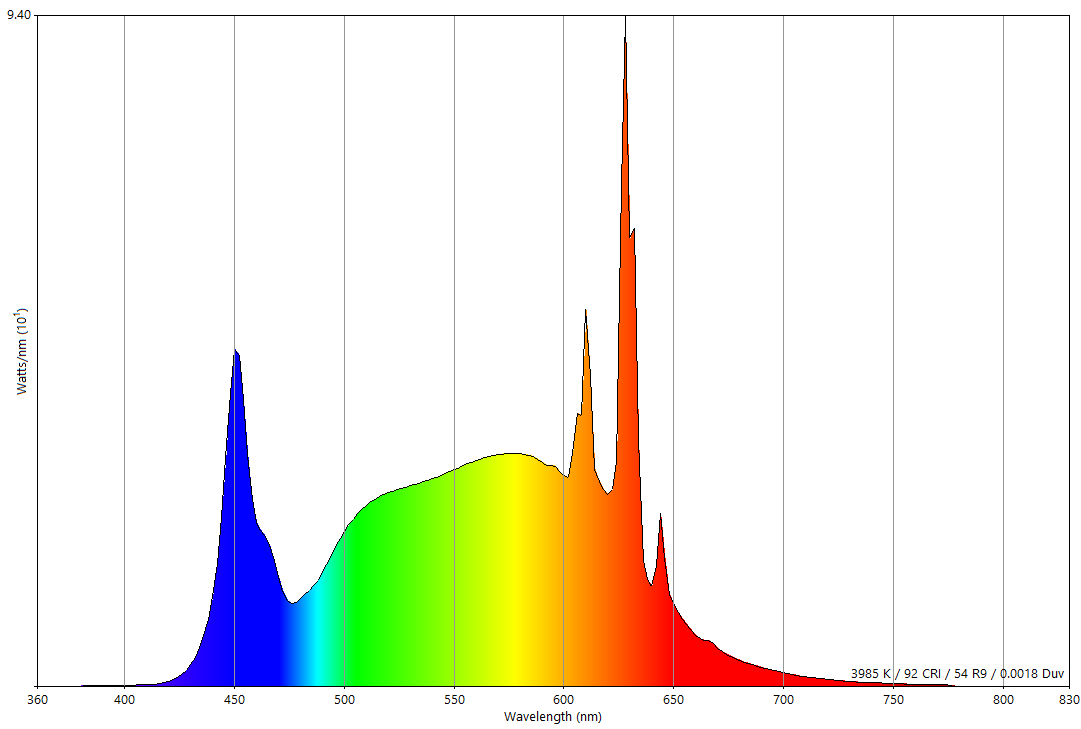

We measure our own spectral data All our luminaires are tested in-house using our NATA-accredited photometric laboratory. We gather full spectral power distributions - no assumptions or default templates, because precise input is essential when designing for human biological effects. |  | ||

| We apply validated circadian metrics We use internationally recognised methods and standards, including:

We also track evolving frameworks like the Circadian Stimulus (CS) model from the LHRC and UL DG 24480, recognising that this is an active area of scientific development. | ||

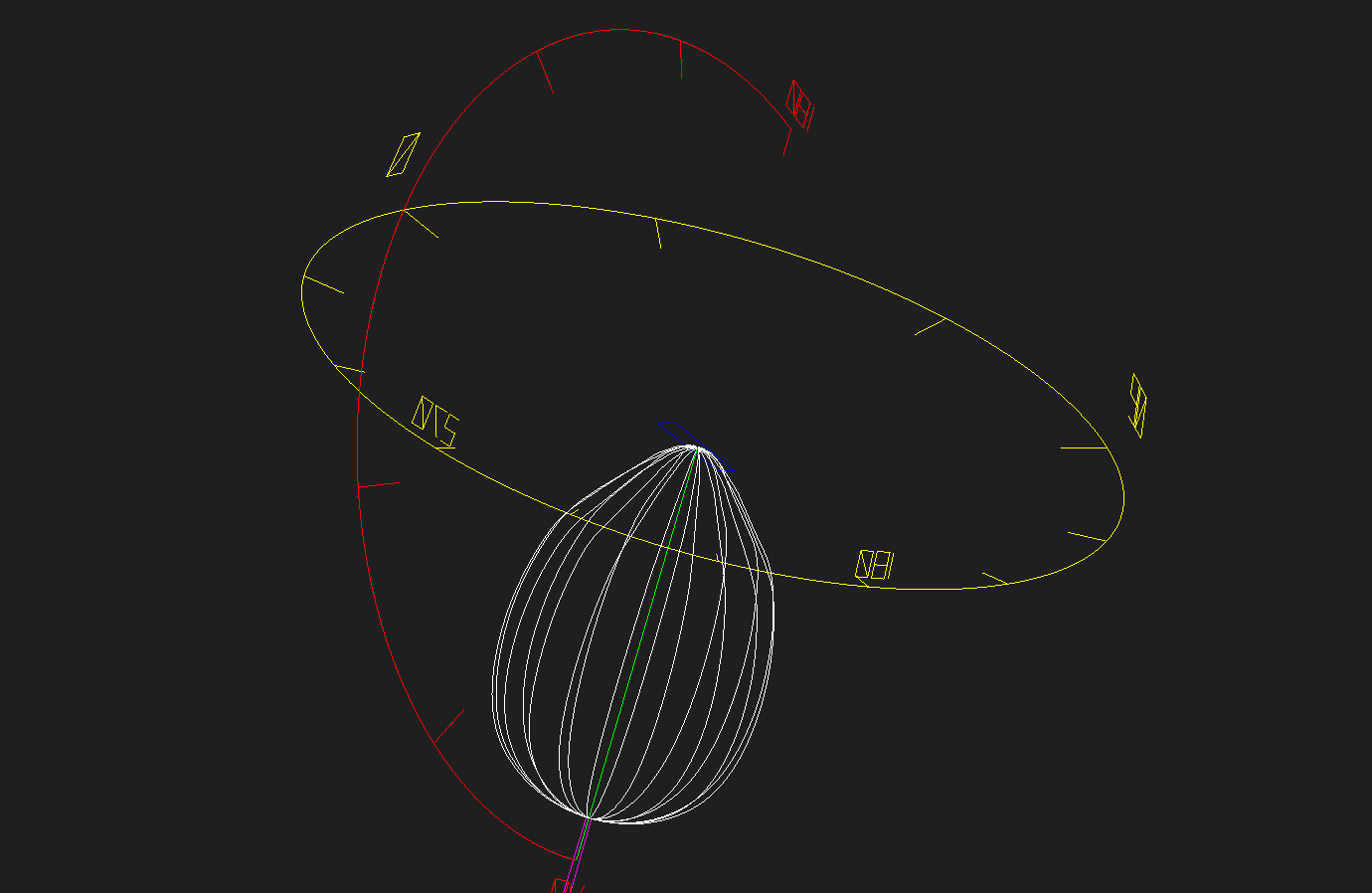

We design for vertical eye-level illuminance Circadian-effective light is delivered primarily via the vertical plane. That’s why we optimise our designs for vertical illuminance at eye level - not just horizontal lux on a desktop. |  | ||

| Local, Evidence-Based Lighting All our work is built on peer-reviewed science and calibrated for real-world Australian and New Zealand conditions. Because human-centric lighting shouldn't be a premium feature - it should be the baseline. | ||